U.S. bankers and interest groups are mobilizing to stop the Biden administration from overhauling how the industry approaches credit card late fees. The exact scope of the regulatory overhaul is currently unknown, but the indication is that the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau (CFPB) expects to implement changes that save consumers billions of dollars a year.

The CFPB uses a complicated formula to determine the maximum amount a financial institution can charge for a late credit card payment. In 2021, the threshold is $30 for the first missed payment, and $41 for each subsequent missed payment within the next six billing cycles. Eighteen of the nation’s 20 top card issuers place late fees on or around the federal threshold–making it the de facto standard. Under the current rules, banks can raise late fees during periods of high inflation without undergoing regulatory scrutiny.

In June, the CFPB asked the industry to provide evidence for how late fees are determined. In its initial statement, CFPB director Rohit Chopra questioned why fees continue to increase in an era of automation. “Is it more reasonable to expect that costs are going down with further advancements in technology every year?” According to American Banker, the nation’s banks and credit unions are “pushing back hard.”

The financial industry says late fees “encourage” discipline by consumers and help cover costs associated with late payments. Many, including Chopra, believe that the industry uses late fees as a profit center rather than a tool to ensure prompt repayment. A March 2022 report published by the agency found that banks charged $12 billion in late fees during 2020. “Many credit card issuers have made late fee penalties a core part of their profit model,” Chopra said in a press release. “Given their current practices, we expect that credit card issuers will hike fees, based on inflation, as limits continue to rise.”

Credit card late fees are a relatively new phenomenon

- A report by the Federal Reserve found that prior to the 1990s, credit card late fees generally ranged “from $5 to $10.”

- In 1996, the Supreme Court ruled that state pricing regulation did not apply to nationally chartered banks. The ruling allowed banks chartered in industry friendly states like Delaware and South Dakota to export higher late fees to states “with tough consumer-protection statutes.”

- After the ruling, credit card late fees increased 119% to over $27 in 2005. In 2008, the highest fees neared $40.

- In 2010 the CFPB ruled that a reasonable late fee was $25 per initial infraction, tied to inflation. The former Assistant Director for Cards and Payments noted that adjusted for inflation, the level was three times where fees were in 1990.

Credit card late fees make up a large proportion of an issuers’ revenue

- A CFPB analysis found that credit card late fees peaked at $14 billion a year in 2019. During COVID, many financial institutions introduced more flexible payment options and fees declined to $12 billion.

- Across the industry, late fees account for 99 percent of all penalties, and make up one-tenth of the $120 billion paid in interest and fees each year.

- Late fees are disportionately charged to low-income individuals and minorities.

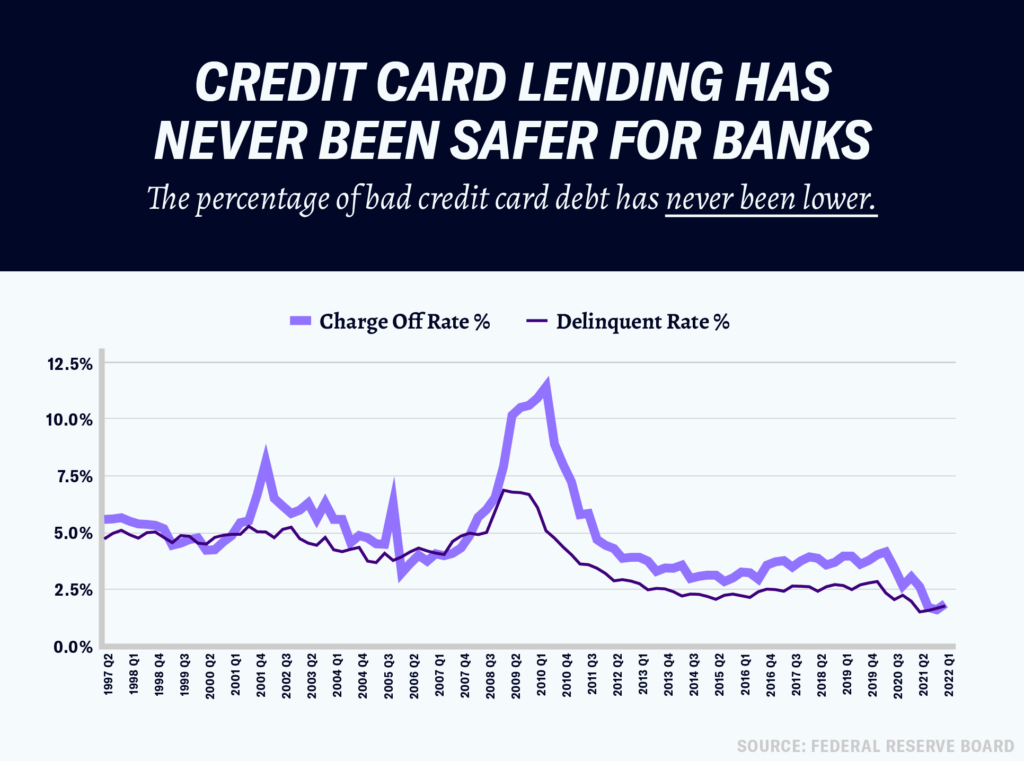

Credit card lending has never been safer for banks

- The industry claims that credit cards are not profitable and late fees are required to offset the cost of discharging bad debt. A joint letter submitted by the American Bankers Association stated that the current level of late payment fees does not cover “the costs associated with late payments.” In fact, the industry argued, late fees should be raised by 60%.

- In 2022, net charge-off rates for consumer credit cards, which measure the percentage of lending banks write off due to non-payment, reached the lowest recorded level since the Federal Reserve began tracking the information in 1985.

- The Delinquency Rate, which measures the proportion of past due accounts, was below 2 percent for the last 12 months–the first time in the metric’s history.

“Late fees,” Chi Chi Wu of the National Consumer Law Center wrote in her comment to the CFPB, “are still an inappropriate, back-end profit center for credit card issuers that obscures the costs of credit cards.” If the CFPB has its way, their use may be further restricted.