Minneapolis Mayor Jacob Frey on Tuesday vetoed an ordinance that would have set minimum rideshare pay rates and guaranteed a host of other labor protections for Uber and Lyft drivers, in what the leader of a rideshare workers’ advocacy group called a “second painful experience” during the last several months.

The ordinance passed by the Minneapolis City Council last week would have set pay rates for drivers to a minimum of $1.40 per mile, $.51 per minute, and $5 per ride. The bill would have also created a city-run resource center for drivers, allowed them to appeal deactivations from the services, and banned the use of gift cards to force riders to use their own names, which drivers’ advocates argue would blunt an increase in crimes against drivers.

The ordinance narrowly passed, two votes short of what’s needed to override a veto. And Frey did veto the legislation, saying it “needs more work.”

“What ultimately played a role in my decision was recognizing that we didn’t have all the data and information that we needed to understand the consequences of the decision we’re making — I don’t want to sign something just to find out a week later that there were problems with it,” Frey told Minnesota Public Radio. “What I’m proposing is: let’s do our homework, let’s do this right.”

But Frey’s veto came after Uber and Lyft had threatened to pull services in Minneapolis, mirroring a tactic they deployed successfully in May against legislation that would have established similar rideshare regulations statewide. In that case, Minnesota Gov. Tim Walz issued his first veto in more than five years as the state’s governor.

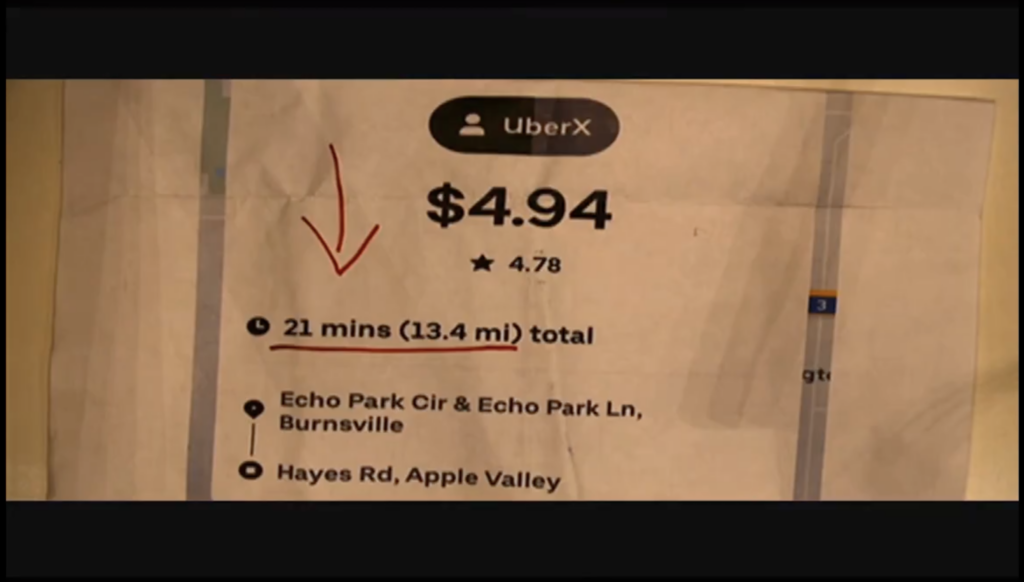

During a Minneapolis city hearing last month, drivers offered emotional testimony in support of increased pay and transparency. One Uber driver, Ahmed Ahmed, displayed a receipt showing that for a 21-minute, 13.4-mile ride between two Minneapolis suburbs, he was paid just $4.94.

“We are hard workers, and we work 12 hours a day for seven days [a week],” Ahmed said at the hearing. “I don’t have time for my kids to take them out.”

Eid Ali, the president of the Minnesota Uber and Lyft Drivers Association (MULDA) advocacy group, said Wednesday that Frey’s veto dealt a second blow to drivers in just a few months.

“It was very devastating because we have hundreds of drivers and thousands of their family members relying on the outcome of this city ordinance,” Ali told More Perfect Union. “It was not the outcome we were waiting for.”

Uber and Lyft’s go-to move

Uber and Lyft drivers all over the world have complained for years about problems including low pay, poor safety, and a lack of transparency regarding fares. A UCLA Labor Center study of New York City rideshare rides released in February found that between February 2019 and April 2022, the increase in fares to Uber and Lyft riders outpaced the increase in pay for drivers, and Uber took large commissions of more than 30 percent on nearly one-third of rides, as opposed to 9 percent of rides just three years prior.

Some states and local governments have pursued extending traditional labor rights to drivers in the industry. In response, Uber and Lyft have a history of issuing — and sometimes following through on — threats to leave areas they serve, including Houston and San Antonio.

The most famous case was in Austin. In 2015, the Austin City Council passed restrictions on Uber and Lyft that effectively treated them as conventional taxis, including safety measures such as fingerprint background checks. In May 2016, Austinites rejected a referendum to overturn some of the regulations — and so Uber and Lyft, which backed the referendum to the tune of $9 million, left Austin.

After Uber and Lyft left, a fleet of new competitors popped up on the market, willing to comply with the new law and by some accounts seamlessly filling the void left by the two biggest rideshare companies. But Uber and Lyft successfully lobbied the much more right-wing Texas state legislature to overturn more stringent local regulations.

Gov. Greg Abbott signed a law in May 2017 creating a “state framework” for rideshare regulations that didn’t include fingerprinting, which he hailed as a “celebration of freedom and free enterprise” by overturning the will of both Austin’s elected representatives and residents themselves.

A few years later, rideshare companies faced a much larger test in California. After they failed to convince the state legislature to exempt them from a 2019 employment law that classified drivers as employees instead of gig workers, giving drivers access to new benefits, they turned to the state’s lax referendum process.

Proposition 22, which would create that exemption for “app-based transportation and delivery companies,” was the most expensive referendum in California state history when it came before voters in 2020. Companies poured more than $200 million into the effort to get the exemption, outspending opponents such as the California Labor Federation tenfold. Repeating a theme, Uber and Lyft also threatened to shut down in California if the proposition didn’t pass.

Voters approved Prop 22 in a win for the companies, but the ultimate fate of the referendum is still tied up in the California state courts.

In nearby Washington, legislation signed by Gov. Jay Inslee in 2022 guarantees rideshare drivers minimum pay rates and benefits while allowing the companies to continue classifying them as independent contractors. An additional law passed this year grants the state’s approximately 30,000 Uber and Lyft drivers paid family and medical leave.

Two disappointments in Minnesota

When Minnesota lawmakers passed minimum pay rates for Uber and Lyft drivers this year, rideshare drivers celebrated by literally lifting up one of the bill’s sponsors, Rep. Omar Fateh, in celebration.

They had reason to be optimistic — after winning full control of state government in November, the Minnesota Democratic-Farmer-Labor (DFL) Party immediately became one of the most actively progressive statehouses in the country. Gov. Tim Walz, who easily won reelection last November, had never vetoed a bill sent to him by the legislature.

But after Uber and Lyft threatened to cut services in Minnesota, Walz caved and vetoed the provision while announcing plans for a “working group” involving drivers, the companies, and others, that will likely suggest more moderate regulations.

“Rideshare drivers deserve fair wages and safe working conditions. I am committed to finding solutions that balance the interests of all parties, including drivers and riders,” Walz said in a May 25 statement. “This is not the right bill to achieve these goals.”

Minneapolis has independently pursued its own regulations over the past several months, according to Council Member Robin Wonsley, the lead author of the ordinance.

While Wonsley said it was unsurprising that Frey vetoed the ordinance, she said she was surprised that he “circumvented the legislative process to strike a pinky promise deal with an exploitative, out-of-state, multibillion-dollar corporation.”

Frey said Tuesday that Uber (but not Lyft) had committed to paying at least $5 per ride and rates consistent with Minneapolis’s $15 minimum wage, though it’s unclear how transparent Uber will be about driver pay—as Wonsley pointed out, the ordinance would have made the process more transparent by requiring the companies to provide drivers and riders with itemized receipts showing how much riders paid and how much drivers received from a given trip.

In lieu of signing the ordinance, Frey said in a statement that “in the coming weeks, we will work in partnership with all stakeholders to do our homework, deliberate, and make sure we put together an ordinance that is data-driven and clearly articulates policies based on known impacts, not speculation.”

Frey’s move was praised in statements from both Uber and Lyft. “Mayor Frey was right to listen to drivers, riders and our communities and reject the proposal,” a Lyft spokesperson said, according to KARE 11. “By attempting to jam through this deeply-flawed bill in less than a month, it threatened rideshare operating within the city.”

Wonsley said the fight isn’t over. “We’re gonna continue following the lead of drivers, which is what prompted us to even bring forward this in the first place,” she told More Perfect Union. “Drivers have been raising these concerns for years. And we want to make sure that we’re following their lead, and also make it clear that we’re not done with the legislative process.”

Ali, the MULDA president and founder, said that while drivers are frustrated and disappointed by the two defeats, he hopes something good comes out of the governor’s commission.

“I’m someone who believes in a second chance, so I don’t give up easily,” Ali told More Perfect Union. “What I’m trying to do is to learn all the angles of this commission and work with the commission, and make sure that we are doing the right thing for hardworking drivers. And hopefully, something positive will come out.”