The derailment of a Norfolk Southern train carrying 20 railcars of toxic chemicals in western Ohio has renewed scrutiny on precision scheduled railroading (P.S.R.)–a controversial management approach that prioritizes profit at the expense of all else.

Since its introduction in the early 1990s, the approach became an effortless way for rail executives and shareholders to inflate profits, while limiting the actual effort of management. At its core, P.S.R. mandates trains to transport bigger and heavier loads with fewer workers.

In practical terms, it means that trains went from 80-90 railcars supported by 5 workers, to 2 workers overseeing 150 railcars or more. This enabled management to effectively invert how much companies spent on workers and how much profit they generated for shareholders. Of course, this came at a cost: safety and reliability. Reports indicate that before it derailed, Norfolk Southern train 32N broke down due to its excessive size.

“The root causes of this wreck,” Railroad Workers United said in a statement released days after the derailment, “are the same ones that have been singled out repeatedly, associated with the hedge fund initiated operating model known as “Precision Scheduled Railroading.”

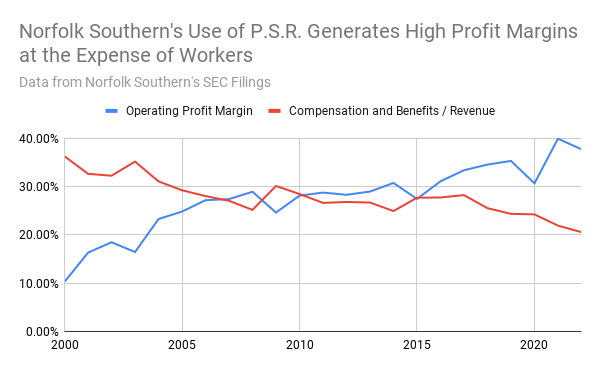

In 2002, Norfolk Southern employed 29,000 people. By the end of 2022, the company had slashed its headcount by 33%. Meanwhile, management more than doubled profit margins.

The industry tracks this through a metric termed an “operating ratio.” For his part, after missing the target in 2020, C.E.O. James Squires was paid a bonus nearly 100x the company’s median salary for achieving Norfolk Southern’s operating ratio goals in 2021. In total, Squires earned $14 million for the year.

One way to look at the impact of P.S.R. is through the lens of employee productivity, which the rail industry measures through a metric called “revenue-ton-miles per employee.” From that perspective, productivity at Norfolk Southern has increased by 30% since 2015.

Business productivity is primarily influenced through two ways: technology or job cuts. There’s little evidence that last decade’s productivity surge is due to a great technological revolution in railroading. Shippers bemoan the railroad’s arbitrary scheduling software in federal testimony, and Northfolk Southern spent millions successfully lobbying against regulations that would have mandated updating Civil War-era braking technology. Rather, the efficiency gains the company experienced were seemingly tied to eliminating over 9,600 jobs during that time.

“They cut their workforce to barebones, and now they’re paying the price for it because the wheels are falling off the train,” Clyde Whitaker of the Sheet Metal Rail Transportation Union told More Perfect Union shortly after the Ohio disaster.

Inspecting a railcar is a largely manual process that involves visually examining the physical railcars for defects. Whitaker says management cut workers who performed the inspections while reducing the time allotted to inspect each car in half. Workers are expected to do the same job as before, with less help, and in half the time. On paper, and to Wall Street, that’s efficiency. In reality, it’s something different. “It’s a rush job now,” he said. “If they don’t hurry up and get this car done, they’ll be fired.”

For years, labor unions and railroad customers have alerted the public and regulators to the destabilizing effects of P.S.R. Both groups watched as the Wall Street-friendly operating model enriched a few while stretching the reliability and safety of America’s rail network.

“Calls for P.S.R. being a Trojan Horse fell and deaf ears,” a V.P. at Univar Solutions, a chemical provider with over $8 billion in annual sales, told the federal government last year. “Shippers and the public’s best interests were outweighed by the inertial weight of the railroad management’s zeal in delivering enormous profits to the investment community.”

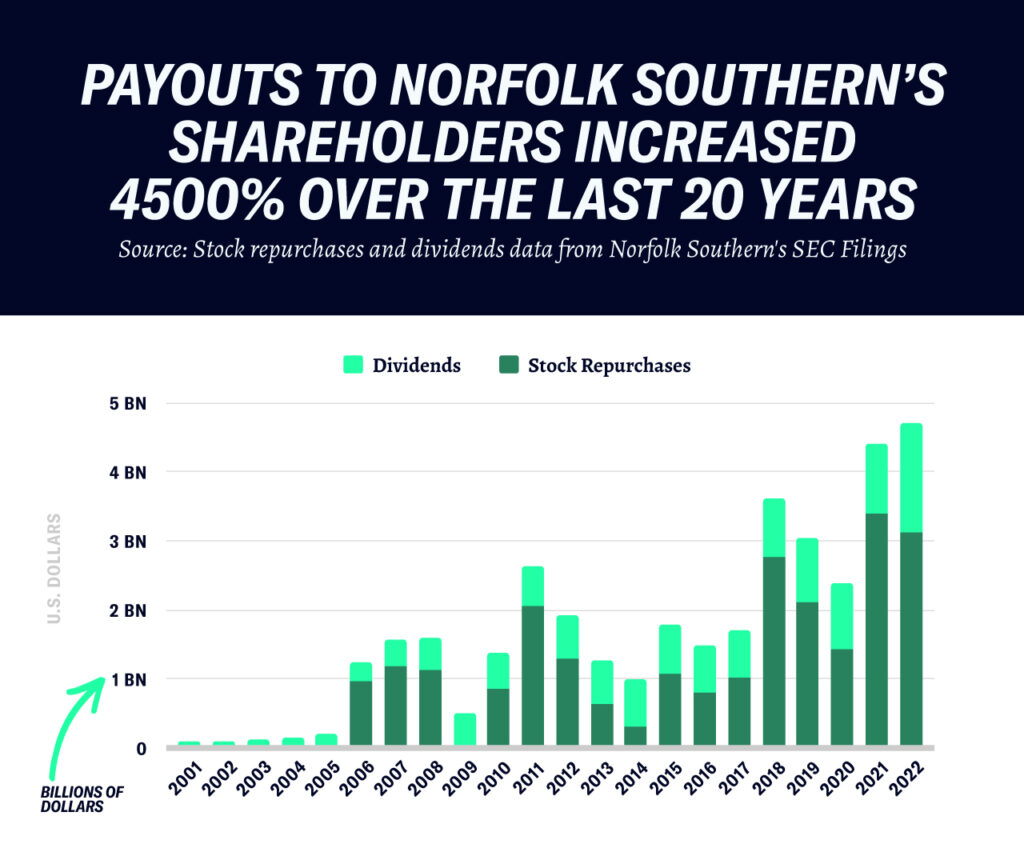

And delivering enormous profits for investors is what P.S.R. does best.

In 2002 Norfolk Southern spent $101 million on dividends and stock repurchases. Two decades later, and with the help of P.S.R., the company allocated $4.7 billion–an increase of over 4500%.

As of right now, it’s too early to tell what the long-term impact of the spill will have on the community. The Ohio river is littered with dead fish while authorities assure residents that the groundwater has not been contaminated. Bloomberg reported that early estimates peg the clean-up costs at $2.7 billion.

That may seem like a staggering amount, but it’s 15% less than Norfolk Southern spent on stock repurchases last year.