America’s largest railroads have transformed a once-staid industry into a profit-generating machine on par with the world’s richest technology companies, even as they drove down conditions for the tens of thousands of workers they employ.

A More Perfect Union analysis of financial filings of major U.S. railroads found that their windfall profits have come at the direct expense of their workforce. In the past two decades, operating profit margins nearly tripled for the major carriers, while the percentage of revenue they spent on labor sunk by double-digits.

Tens of thousands of American rail workers have gone three years without a raise amid a contract dispute with the major carriers. The industry has rejected their calls for sick leave, guaranteed time-off, and a range of other improvements, even as their profit margins swelled.

In 2001, leading American freight carriers CSX, KC Southern, Norfolk Southern and Union Pacific earned average operating margins of about 15%. That means that after accounting for all the costs associated with running a railroad (including money spent on compensation & benefits), for every $100 of revenue, investors were left with $15 of profit. Twenty years later that number has skyrocketed to over $41.

During that same time period, the percentage of revenue spent on labor saw a sudden and drastic decline. In 2001, the four railroads spent about $8.7 billion on compensation and benefits to generate $25.6 billion. In 2021 the companies spent 10% more on labor but brought in nearly double the amount of revenue. It’s “insane to think about,” said Matt Reustle, a popular investing commentator and former transportation analyst, earlier this year.

Technology and more efficient diesel engines have made the rail industry more efficient, but the reduction in headcount has an outsized impact on operating profit margins. According to the Presidential Emergency Board, which analyzed the dispute, “the Carriers maintain that capital investment and risk are the reasons for their profits, not any contributions by labor.” As the graph below demonstrates, there’s a clear inverse relationship between a company’s profit margin relative to the amount it spends on labor.

The revolution can be traced back to executive Hunter Harrison, who pioneered what’s commonly referred to as “precision scheduling” — a business model based in part on longer trains and fewer workers.

In 2000, Union Pacific employed 50,000 people and generated $11.8 billion. Today, Union Pacific, employs almost 18,000 less people, but manages to earn 85% more in revenue each year. The situation is common across the industry. Trains that were once staffed with five workers are now staffed with two, and carriers hope to cut that to one. Workers themselves are caught in constant flux. Nearly all employees are on-call virtually around the clock, expected to report to work within 90 minutes for shifts that can last nearly 80 hours. “That does not include the time that you’re sitting at the away-from-home terminal,” said rail worker Michael Paul Lindsey. “You might be away from home subject to the railroad not with your family for 120 hours in a week.”

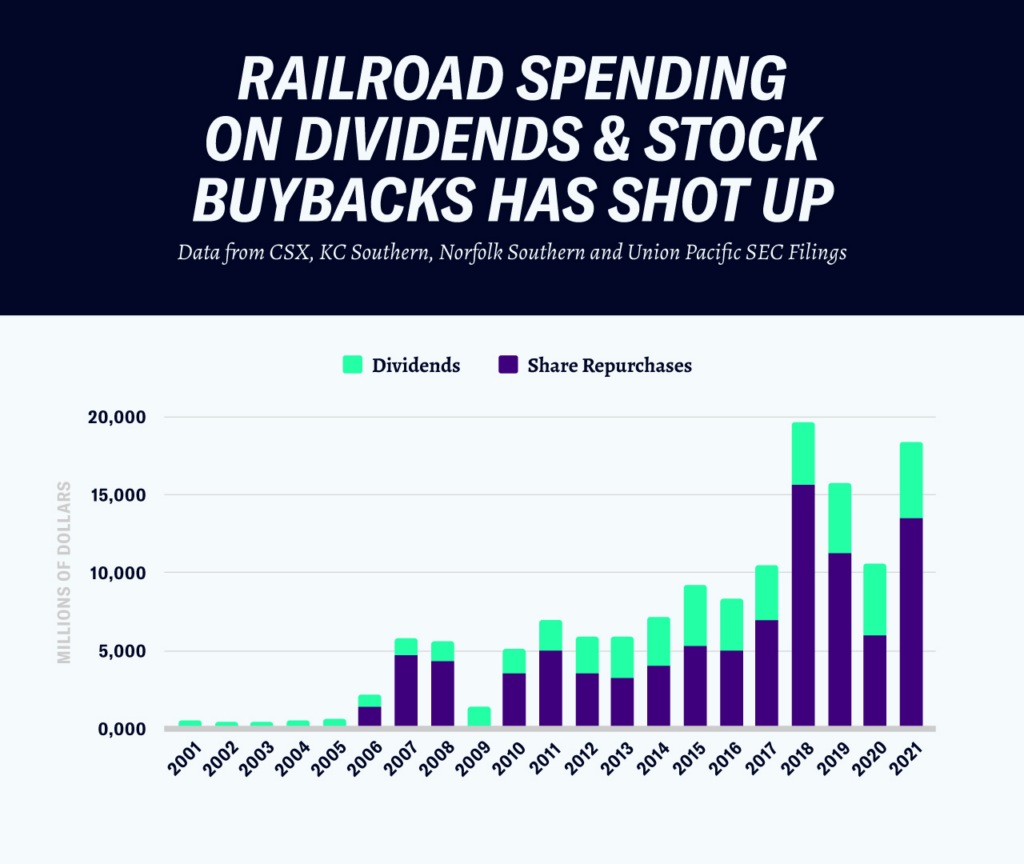

The data suggest that the money once spent on fully staffing locomotives is now spent on enriching shareholders through dividend payments and stock repurchases.

In the past, most rail executives at the four surveyed railroads rewarded investors with modest yearly dividends. In 2009, the rail industry’s operating margins overtook what the companies spent on wages and benefits relative to revenue. The shift had a massive impact on how much profit the firms made and how executives managed the company. From 2001-2009, the four rail firms spent $17 billion on dividend payments and stock repurchases. In the 8 years after the inflection point, that amount increased by nearly 4.5 times.

Share repurchases—the practice of executives using profits to buy the company’s stock and boost its price—were once effectively non-existent. Today, management regularly spends upwards of $10 billion a year on share repurchases. Starting in 2010, the four companies have delivered nearly $124 billion to shareholders in dividends and stock repurchases. During that same time, all American railroads have paid out a staggering $196 billion.

BNSF, the nation’s largest rail carrier by 2021 revenue, is not immune from the trends. The railway, which is owned by Warren Buffett’s Berkshire Hathaway, recently embraced precision scheduling. This year the company posted the best operating margin in at least 21 years, while the percentage of revenue spent on labor fell to its lowest. As part of the operational makeover, the company introduced a draconian point-based attendance system which results in workers getting just one day off each month.

America’s major freight railroads began halting shipments and snarling the supply chain on Monday in an effort to pressure Congress to impose a labor contract that’s friendly to the industry. If no agreement is reached by Thursday, railroads will legally be able to lock-out workers, and rail workers will legally be able to authorize a strike. Either action could have severe consequences for U.S. supply chains.

“I have never seen them disregard their employees like this,” said Dennis Pierce, president of one of the largest rail unions, BLET. “I’ve never seen them treat them this bad in the workplace, and I’ve never seen them this adamant at the bargaining table that they want everything.”

Paula Pecorella contributed to this report.