By Jordan Zakarin

An explosive new document obtained by More Perfect Union reveals that supermarket giant Kroger has long been aware that its workers can’t afford basic necessities and struggle to survive.

The internal presentation, titled “State of the Associate” and marked “confidential,” warned Kroger executives in 2018 that hundreds of thousands of employees live in poverty and rely on food stamps and other public aid as a result of the company’s low pay.

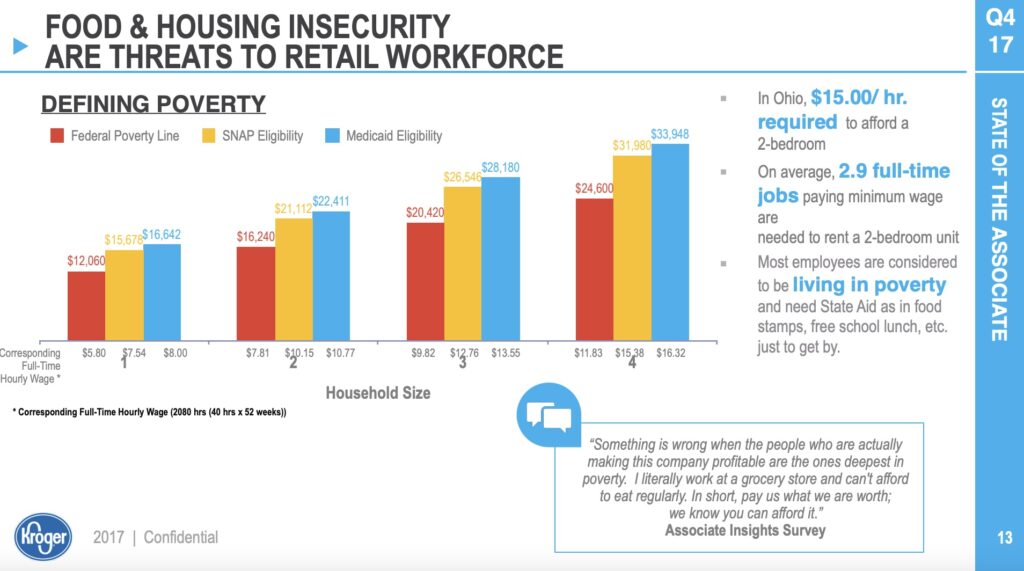

“Most employees are considered to be living in poverty and need State Aid as in food stamps, free school lunch, etc. just to get by,” one slide warned.

The presentation is peppered with quotes from unnamed employees that foretell the internal labor uprising that would come a few years later. “Something is wrong when the people who are actually making this company profitable are the ones deepest in poverty,” said one employee quoted from an internal survey. “I literally work at a grocery store and can’t afford to eat regularly. In short, pay us what we are worth; we know you can afford it.”

With $4 billion in projected profits in 2021, Kroger is America’s largest grocery chain, overseeing 16 brands including Ralphs, Food 4 Less, and Fred Meyer. CEO Rodney McMullen made $22 million in 2020, more than 900 times as much as the median worker. Kroger has one of the largest CEO-worker pay gaps of any major U.S. company.

Kroger representatives did not respond to a request for comment.

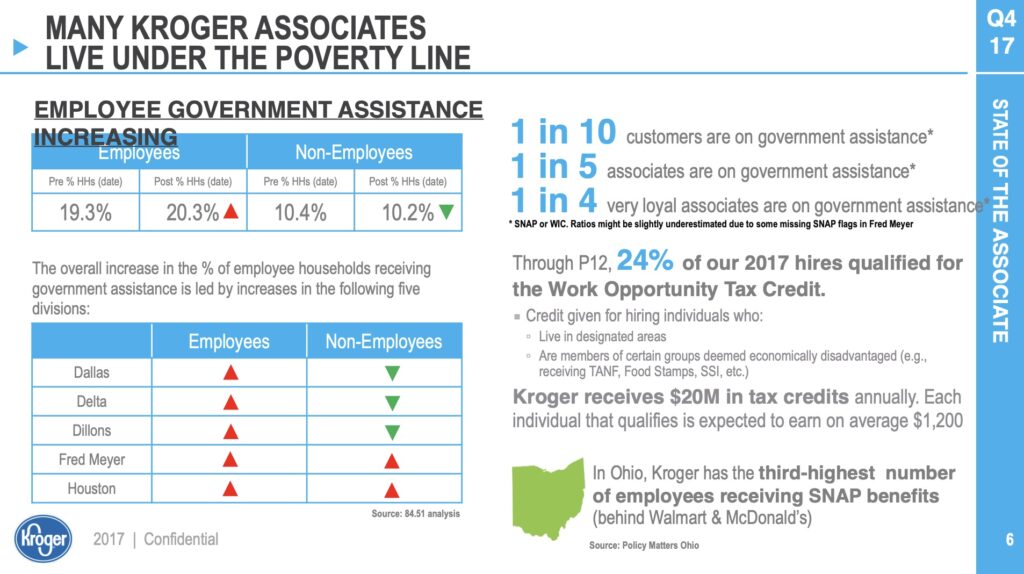

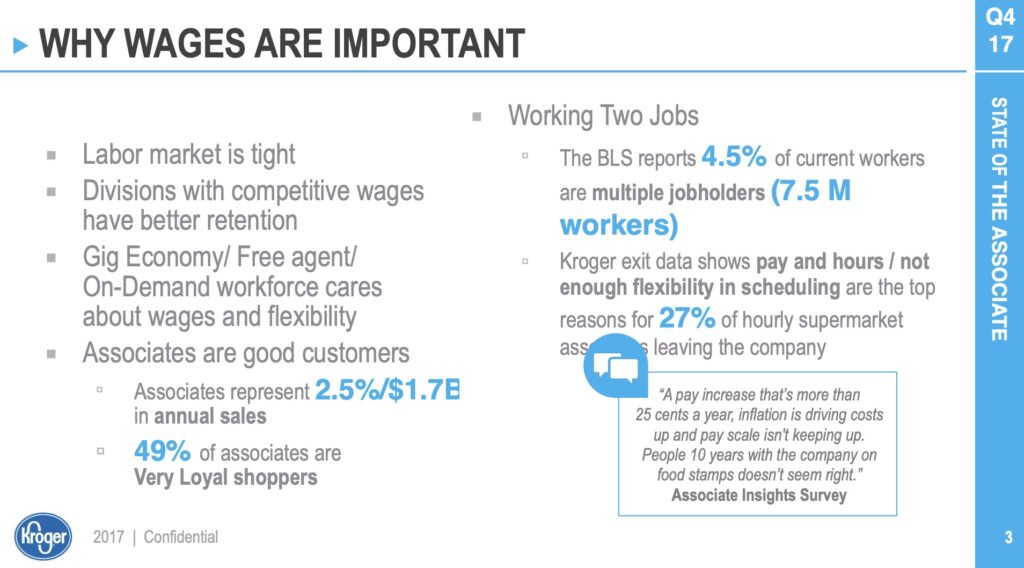

The presentation found that at least 1 in 5 Kroger associates were on food stamps, including at least 25% of “very loyal” associates who frequently also shop at Kroger stores. It said low wages were cited by 27% of workers who quit the company.

The document offered a graph of the federal poverty line and the hourly wages that would qualify workers for food stamps and Medicaid. It also noted that in Ohio, where Kroger is based, a worker needed to earn $15/hour to afford a basic two-bedroom apartment. The presentation further noted that in 2016, Kroger received $20 million in tax incentives from the state of Ohio.

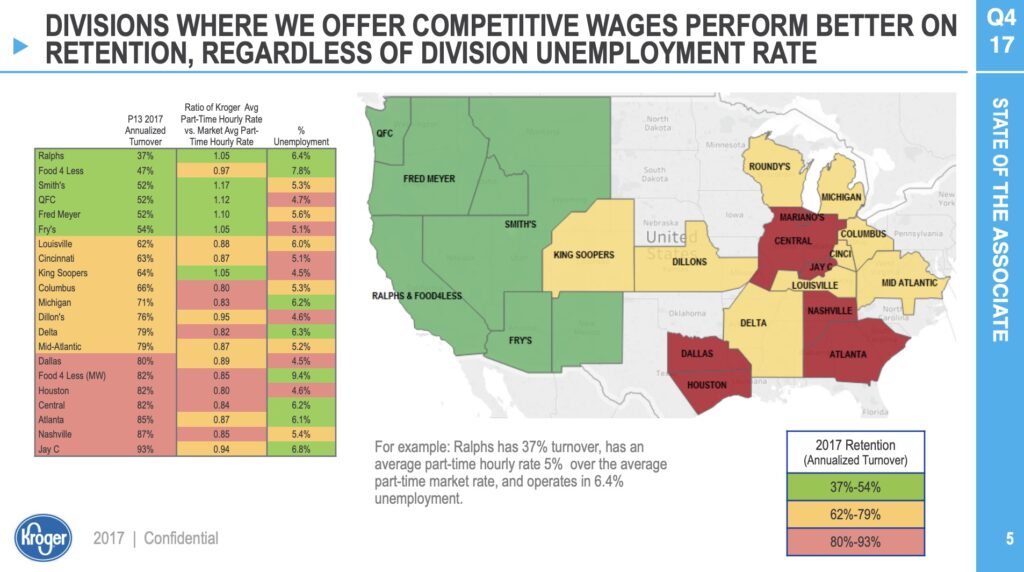

The document includes an internal analysis which found the stores that increased wages also had better employee retention and less turnover.

It quoted another unnamed worker who rebuked Kroger’s lack of pay hikes for long-time workers: “A pay increase that’s more than 25 cents a year, inflation is driving costs up and pay scale isn’t keeping up. People 10 years with the company on food stamps doesn’t seem right.”

Four years later, in late 2021, salary data from Payscale.com indicated that the average pay for a Kroger on-site employee is $12.11. Earlier in the year, Kroger said that it was lifting its average wage to $16, but did not indicate whether that number was skewed by salaries earned by white collar employees. Many states where Kroger operates have raised their minimum wages.

On Wednesday, about 8,700 employees of the Kroger-owned King Soopers grocery chain in Colorado launched a three-week strike to demand better wages and benefits.

The company’s “last, best, and final” contract offer to UFCW Local 7, the union representing the workers in Colorado, included a starting wage of $16 an hour, just 13 cents above the minimum wage in Denver. According to the National Low Income Housing Coalition, renting a two-bedroom apartment on a single full-time job requires a $27.50 an hour wage. In the Denver metropolitan area, that figure jumps to $30.87 and up to $33.15 in Boulder.

The Kroger source who supplied the 2018 presentation indicated that much of the company’s focus was on keeping wages down while burnishing the company’s reputation. In 2018, Kroger launched its Zero Hunger Zero Waste campaign, which seeks to help low-income customers attain government assistance, offers grants to nonprofits, and run food drives in the local community.

A survey released this week by the Economic Roundtable indicated that three-quarters of Kroger employees are food insecure and that 14% of the chain’s workforce experienced homelessness in the past year.

In a section of the 2018 report titled “Turning Our Insights Into a Leadership Call to Action,” executives are advised to recruit and train diverse associates, but also to “continue to develop automation, leveraging technology at store level.”

Last year, Kroger embarked on a massive project to build robot-staffed warehouses for online orders, with each warehouse costing at least $55 million. It also launched a drone delivery service.