Three weeks after Kroger upended America’s grocery market by announcing it intended to purchase Albertsons, I talked to a man whose job is facilitating these types of transactions. He’d never been involved with a deal of this size — $24.6 billion. Nor had he ever been involved in a deal that could reshape the economy — the second-largest grocer acquiring the fourth. He has spent most of his professional career working with business owners looking to cash out. Some sell to individuals; others sell to institutional investors — like private equity firms. In the grocery merger, private equity firm Cerberus Capital Management is looking to cash out by pushing the sale of Albertsons to Kroger.

Though Albertsons is publicly held, Cerberus is the de facto owner. With 30 percent of the shares, Cerberus is the largest of five private investment firms that control the grocer. Buried in the acquisition announcement was a startling tidbit: Albertsons planned to borrow billions of dollars and spend nearly three-quarters of its available cash paying out a special dividend to shareholders. In doing so, the company would empty its wallet and take on $1.5 billion in new debt; shareholders, led by Cerberus, would receive up to $4 billion.

“Actions like that,” the mergers and acquisition advisor told me, “are why people hate private equity.” Albertsons’ management team, led by Cerberus, apparently looked at the grocery landscape — which now requires billions of dollars in investments to remodel stores, enable online shopping, and retain workers — and decided the best use of the company’s money is to pay themselves $4 billion. And they may still get away with it.

Last week, a Washington state judge halted Albertsons’ dividend payment until the court can further review the transaction. The state’s attorney general, Bob Ferguson, sued to stop the merger, along with three other Democratic state attorneys general from California, Illinois and the District of Columbia. “Putting the brakes on this $4 billion payment is the right thing for Americans shopping at their local grocery store,” Ferguson said in a statement. The judge’s ruling only delays the dividend payment temporarily, buying the government a few days to prepare its case.

The crux of the AG’s argument hinges on the timing and impact of the special dividend on Albertsons’ business operations. According to the merger agreement, the dividend payout to Cerebrus was to take place on November 7, just weeks after the merger was announced and arguably years before the deal would close. Given the political firestorm facing the agreement, it’s possible the deal doesn’t close at all. “We have serious concerns about the proposed transaction between Kroger and Albertsons,” Sen. Amy Klobuchar, Democratic chair of a Senate antitrust subcommittee, said in a joint statement with Sen. Mike Lee, the panel’s top Republican. The lawmakers have scheduled a hearing for later this month.

It turns out that unfettered greed appears to be bad for business. The proposed $4 billion special dividend — which amounts to roughly 80 percent of what Albertsons owes in worker pension funds — would deplete the company’s cash reserves and saddle it with over a billion dollars of additional debt. Moody’s, a rating agency that evaluates corporate debt, cited the company’s “lower cash balances” when it reduced its already poor credit rating to junk status after the announcement. That means that if the deal falls apart, but the dividend goes through, the remaining company would be left with more debt, less cash, and higher borrowing costs. “They’re essentially looting this company,” Jonathan Williams, a representative of the United Food and Commercial Workers Local 400, told the Washington Post.

The state attorneys general lawsuits seem to be trying to stop Albertsons from joining Toys “R” Us as one of those retailers that people point to later and say, “Well, at least we didn’t do something that stupid.” In 2004, Toys “R” Us was a modestly profitable retailer struggling to adjust to the rise of e-commerce. A year later it was acquired by private equity, loaded up with $6 billion worth of debt, and saddled with $450 to $500 million in interest payments–more than three times what they were before. Despite selling 20 percent of the toys in America, and maintaining revenue throughout the Great Recession, the company declared bankruptcy in 2018. The debt, Bloomberg later reported, was “a burden that left it ill-equipped to handle competition from Walmart Inc. and Amazon.com Inc.” Similar to Cerberus, private equity backers of Toys “R” Us made out well — despite the company’s difficulties. According to one analysis by The Atlantic, the management fees that private equity companies charged Toys “R” Us for the privilege of their advice far exceeded any loss they took on the loans.

Prior to the special dividend announcement, Albertsons was on solid financial footing. Same-store sales, a key financial metric in the grocery industry, surpassed rival Kroger for six of the last eight quarters. That growth generated significant profits for the company, which management used to pay down debt and transfer over $300 million to shareholders through yearly common and preferred dividend payments. At the same time, Albertsons spent almost half a billion dollars paying for interest on its debt.

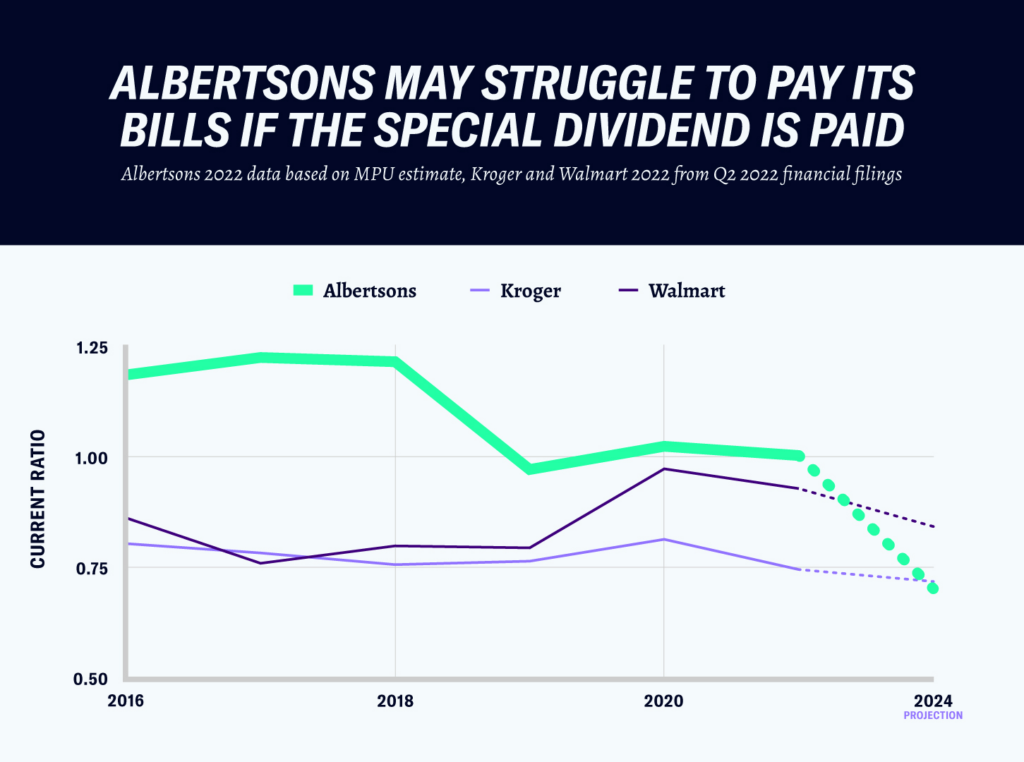

Since 2016, Albertsons’ current ratio has typically hovered around 1.0—meaning that management almost always has enough money on hand to pay its short-term bills. Current ratio is one way to evaluate a company’s high-level ability to pay off its debts and fund daily operations. If a current ratio is under one, it’s considered negative. The company may have to borrow money to pay its short term expenses.

Giant retailers like Walmart and Kroger, who together control over one quarter of the grocery market, are able to operate with negative current ratios. Unlike Albertsons, the duo has the market power to demand sixty or ninety days to pay bills–instead of a standard 30 days. This small detail allows Walmart and Kroger to push their bills out and operate with negative current ratios.

If the special dividend is paid, but the merger does not happen, Albertsons could find itself with a current ratio below Walmart or Kroger–without the market power. With lower cash reserves, a quick back-envelop estimate of the company’s current assets and liabilities puts its new current ratio at .7. That’s a decline of 35 percent from its five year average. The deal would put the company into similar shape as Toys “R” Us, whose current ratio fell 32 percent after private equity loaded the firm with debt.

The Wall Street Journal recently reported that the new fiscal environment has the financial industry bracing for nearly 200 corporate defaults over the next few years. If the special dividend is blocked, there’s a good chance Albertsons won’t be one of them. If it goes through, and the merger fails, it could find itself alongside Toys-R-Us as a case study in retail mismanagement.